- Terms & Conditions|

- Privacy Policy & Data Protection|

- Contact|

- Accesssibility|

- Copyright 2018 Yale University

Select documents to open

|

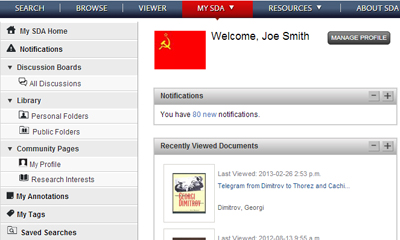

MySDA: A Centralized Workplace for Scholars, Researchers, and Students

Learn more about MySDA in the SDA User Guide. Click here to register a new MySDA account. |

Log In to SDA

|